A Critique of Website Traffic Fingerprinting Attacks

Website traffic fingerprinting is an attack where the adversary attempts to recognize the encrypted traffic patterns of specific web pages without using any other information. In the case of Tor, this attack would take place between the user and the Guard node, or at the Guard node itself.

There are two models under which these attacks are typically studied: The "closed world" scenario, and the "open world" scenario. In the "closed world" scenario, the only traffic patterns the classifier ever sees are for web pages that it has already been trained on, and it typically must successfully label all of them. This is meant to simulate situations where users only use Tor for viewing a small set of censored web pages and nothing else. The "open world" scenario is slightly more realistic in that it attempts to examine the ability of the adversary to recognize a few censored pages out of a much larger set of uncensored pages, some of which it has never seen before.

It is important to note that in both models, these papers are reporting results on their ability to classify individual pages and not overall websites, despite often using the terms website and webpage interchangeably.

The most comprehensive study of the statistical properties of this attack against Tor was done by Panchenko et al. In their "closed world" study, they evaluated their success rates of classifying 775 web pages. In their "open world" study, they classified a handful of censored pages in 5000 page subsets of 1,000,000 total web pages.

Since then, a series of smaller scale follow-on attack papers have claimed improved success rates since Panchenko's study, and in at least two instances these papers even claimed to completely invalidate any attempt at defense based only on partial results.

While there may have been some improvements in classifier accuracy in these papers over Panchenko, defenses were "broken" and dismissed primarily by taking a number of shortcuts that ignore basic properties of machine learning theory and statistics in order to enable their claims of success.

Despite these subsequent improvements in these attacks, we are still skeptical of the efficacy of this attack in a real world scenario, and believe that only minimal defenses will be needed to ensure the attack continues to be unusable in practice.

This post will be divided into the following areas: First, we will attempt to distill the adversary model used by this body of work, and describe the adversary's goals. Then, we will review the basic properties of machine learning theory and statistics that govern classifier accuracy and real-world performance. Next, we will make these properties concrete by briefly discussing additional real-world sources of hidden complexity in the website traffic fingerprinting problem domain. We will then specifically enumerate both the useful contributions and the shortcuts taken by various work to date. Finally, we will conclude with suggestions and areas for improvement in future work.

Pinning Down the Adversary Model

Website traffic fingerprinting attack papers assume that an adversary is for some reason either unmotivated or unable to block Tor outright, but is instead very interested in detecting patterns of specific activity inside Tor-like traffic flows.

The exact motivation for this effort on behalf of the adversary is typically not specified, but there seem to be three possibilities, in order of increasing difficulty for the adversary:

- The adversary is interested in blocking specific censored webpage traffic patterns, while still leaving the rest of the Tor-like traffic unmolested (perhaps because Tor's packet obfuscation layer looks like something legitimate that the adversary wants to avoid blocking).

- The adversary is interested in identifying all of the users that visit a small, specific set of targeted pages.

- The adversary is interested in recognizing every single web page a user visits.

Unfortunately, it seems that machine learning complexity theory and basic statistics are heavily stacked against all three of these goals.

Theoretical Issues: Factors Affecting Classification Accuracy

Machine Learning theory tells us that the accuracy of a classifier is affected by four main factors: the size of the hypothesis space (ie the information-theoretic complexity of the classification categories), the accuracy of feature extraction and representation (the bias in the hypothesis space), the size of the instance space (the world size), and the number of training examples provided to the classifier.

Bounds have actually been established on the effect of each of these areas to the likelihood of achieving a given accuracy rate, and any good undergraduate course in Machine Learning will cover these topics in detail. For a concise review of these accuracy bounds, we recommend Chapters 5 and 7 of Machine Learning by Tom Mitchell.

The brief summary is this: as the number and/or complexity of classification categories increases while reliable feature information does not, the classifier eventually runs out of descriptive feature information, and either true positive accuracy goes down or the false positive rate goes up. This error is called the bias in the hypothesis space. In fact, even for unbiased hypothesis spaces, the number of training examples required to achieve a reasonable error bound is a function of the number and complexity of the classification categories.

It turns out that the effects of all of these factors are actually observable in the papers that managed to study a sufficient world size.

First, for the same world size and classifier technique, every work that examined both the open and closed worlds reports much higher accuracy rates for the open world than for the closed world. This is due to the higher hypothesis space complexity involved in labeling every page in the closed world, as opposed to labeling only a very small subset of censored targets in the open world. This confirms the above machine learning theory, and tells us that that an adversary that is attempting to recognize every single web page in existence is going to have a very difficult time getting any accuracy, as compared to one who is classifying only a select interesting subset.

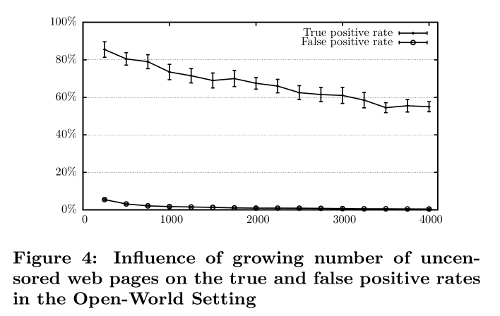

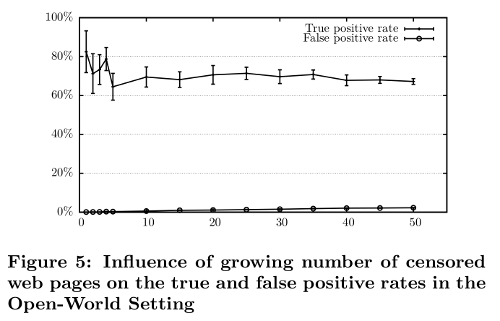

It is also clearly visible in Panchenko's large-scale open world study that increasing the world size contributes to a slower, but still steady decline in open world accuracy in Figure 4 below. The effect of the hypothesis space complexity (increased number of pages to classify) on the open world can also be seen in the rising false positive rates of Figure 5 below (this rise may seem small, but in the next section we will show how even tiny increases in false positives are in fact devastating to the attack).

Every other attack paper since then has neglected to use world sizes large enough to observe these effects in sufficient detail, but again, machine learning theory tells us they are still there, just beyond the published data points.

Practical Issues: False Positives Matter. A Lot.

Beyond classifier accuracy and the factors that affect it, the practical applicability of the website traffic fingerprinting attack is also affected by some basic statistical results. These statistics (which have been examined in other computer security-related application domains of machine learning) show that false positives end up destroying the effectiveness of classification unless they are vanishingly small (much less than 10^-6).

It actually turns out that false positives are especially damaging to this attack, perhaps even more so than most other application domains. In the website traffic fingerprinting attack, false positive results are a built-in property of the world: if one or more pages' traffic patterns are similar enough to a target page's pattern to trigger a false positive, these sets of pages will always be misclassified as the target page every time that traffic pattern is present. Unlike end-to-end timing correlation, the adversary does not get to benefit from information derived from repeated visits (except in narrow, contrived scenarios that we will address in our literature review below).

What's more is that this also means that small world sizes directly impact the false positive rate. As you increase the world size, the likelihood of including a page that matches a traffic stream of your target page also increases.

To demonstrate the damaging effects of false positives on the attack, we will now consider the effects of false positives on the adversary's two remaining feasible goals: flagging users who visit a specific controversial web page over Tor, and censoring only a subset of Tor-like traffic.

In the event where the adversary is attempting to recognize visits to highly sensitive material (such as a specific web page about a particular protest action) and is interested in gathering a list of suspects who visit the web page, it is easy to see that even with very high accuracy rates, the suspect list quickly grows without bound.

To see this, note that the probability of at least one false positive over N independent page loads is given by 1 - (1-fp)^N, where fp is the probability of a false positive.

Even with a false positive rate as low as 0.2% (which is typical for this literature, and again is also lower than reality due to small world sizes), after performing just N=100 different page loads, 18% of the userbase will be falsely accused of visiting targeted material at least once. After each user has performed N=1000 different page loads, 86.5% of that user base will have been falsely accused of visiting the target page at least once. In fact, many of these users will be falsely accused much more frequently than that (as per the Binomial Distribution).

If instead of trying to enumerate specific visitors, the adversary is trying to interfere with the traffic patterns of certain web pages, the accuracy value that matters is the Bayesian Detection Rate, which is the probability that a traffic pattern was actually due to a censored/target page visit given that the detector said it was recognized. This is written as P(Censored|Classified).

Using Bayes Theorem, it is possible to convert from the true and false positive rates of P(Classified|Censored) and P(Classified|~Censored) to the Bayesian Detection Rate of P(Censored|Classified) like so:

P(Censored|Classified) =

P(Classified|Censored)*P(Censored) /

(P(Censored)*P(Classified|Censored) +

P(~Censored)*P(Classified|~Censored))

Under conditions of low censorship (0.1% -- such as when the Tor traffic successfully blends in with a large volume of innocuous Internet traffic, or when Tor is used for both censorship circumvention and general privacy), with a true positive rate of 0.6 and a false positive rate of 0.005, we have:

P(Censored|Classified) = 0.6*.001/(.001*0.6+.999*.005)

P(Censored|Classified) = 0.10

P(~Censored|Classified) = 1 - P(Censored|Classified)

P(~Censored|Classified) = 0.90

This means that when a traffic pattern is classified as a censored/target page, there is a 90% chance that the classifier is actually telling the adversary to interfere with an unrelated traffic stream, and only a 10% chance that the classifier was actually correct.

This phenomenon was explored in detail in the Intrusion Detection System literature, and is the reason why anomaly and classification-based antivirus and IDS systems have failed to materialize in the marketplace (despite early success in academic literature).

Practical Issues: Multipliers of World Size are Common

Beyond the above issues, there are a number of additional sources of world size and complexity in the website traffic fingerprinting problem domain that are completely unaddressed by the literature.

Again, it is important to remember that despite the use of the word "website" in their titles, these attacks operate on classifying instances of traffic patterns created by single pages, and not entire sites. For some sites, there may be little difference between one page and another. For many sites, the difference between component pages is significant.

It is also important to note that the total number of pages on the web is actually quite larger than the number of items indexed by Google (which is quite a bit larger than even the 1,000,000 page crawl used by Panchenko). In particular, the effects of dynamically generated pages, unindexed pages, rapidly updated pages, interactive pages, and authenticated webapps have been neglected in these studies, and their various possible traffic patterns contribute a very large number of additional web traffic patterns to the world, especially when the different manners in which users interact with them are taken into account.

Beyond this, each page actually also has at least 8 different common traffic patterns consisting of the combination of the following common browser configurations: Cached vs non-cached; Javascript enabled vs disabled; adblocked vs non-adblocked. In each of these combinations, different component resources are loaded for a given page. In fact, the cached vs non-cached property is not just binary: arbitrary combinations of content elements on any given page may be cached by the browser from a previous visit to a related resource. What's more, in Tor Browser, either restarting the browser or using the "New Identity" button causes all of this caching state to be reset.

In addition, similarities between non-web and web traffic also complicate the problem domain. For just one example, it is likely that an open tab with a Twitter query in it generates similar traffic patterns to a Tor-enabled XMPP or IRC client.

All of these factors increase the complexity of the hypothesis space and the instance space, which as we demonstrated above, will necessarily reduce the accuracy of the attack in both theory and practice.

Literature Review: Andriy Panchenko et al

Title: Website Fingerprinting in Onion Routing Based Anonymization Networks

As mentioned previously, Panchenko's work (actually the first work to successfully apply website traffic fingerprinting to Tor) is still the most comprehensive study to date.

Here is a brief list of its strengths:

- The world sizes are huge.

5000 page subsets of 1,000,000 pages may still have representational issues compared to the real world, but this is still the largest study to date. - Careful feature extraction (hypothesis space construction).

The reason why this work succeeded where earlier works failed is because rather than simply toss raw data into a machine learning algorithm, they were extremely careful with the representation of data for their classifiers. This likely enabled both the efficiency that allowed such a large world size, and reduced the bias in the hypothesis space that would otherwise lead to low accuracy and high false positives at such large world sizes. - In the "open world", they varied the type of censored target sites to evaluate accuracy.

Instead of merely picking the target pages that were easiest to classify (such as video sites), they varied the type of target pages and explored the effects on both true and false positive accuracy. None of the other literature to date has examined this effect in detail. - They are careful to tune their classifiers to minimize false positives.

Modern classifiers typically allow you to trade off between false positives and false negatives. Given how deeply false positives impact the adversary's goals, this is very important. - They demonstrate knowledge of all of the factors involved in PAC theory and practical classifier accuracy.

All of the other papers to date simply omit one or more of the following: data on feature extraction, the contribution of individual features to accuracy, the number of training examples, the effect of target size on both the open and closed world, the effect of target page types on accuracy, and the effects of world size on accuracy.

While impressive, it does miss a few details:

- It fails to acknowledge that false positives are a property of specific sites.

In reality, nearly every false positive they experienced in a given subset of 5000 pages is a false positive that will likely appear in a classifier that is run against the entire 1,000,000 page dataset. They probably should have tallied the total false positives over multiple runs for this reason, and analyzed their properties. - It still fails to provide a realistic adversary model in order to justify claims that the attack actually accomplishes what the adversary wants.

Literature Review: Kevin P. Dyer et al

Title: Peek-a-Boo, I Still See You: Why Efficient Traffic Analysis Countermeasures Fail

This work attempts to evaluate several defenses against the website traffic fingerprinting attack, and also attempts to evaluate an "idealized best case" defense called BuFLO.

On the positive side, the work makes the following contributions:

- It creates an ideal high-overhead tunable defense (BuFLO) that can be compared against other practical defenses.

- It is quite clear about its definitions of accuracy and experimental setup.

- Source code is provided!

However, the work had the following rather serious shortcomings:

- Close world only, and a very small closed world at that.

This is the single largest issue with this attack paper. You cannot claim that all defenses are broken forever if a classifier is only able to somewhat correctly classify 500 pages or less (and only 128 pages in their defense studies!), even in a closed world. - Exaggerated claims give no credit to (or detailed analysis of) relative strengths of defenses.

Despite the fact that their exaggerated claims are made possible due to their small world size of only 128 pages, the authors do not acknowledge that some light weight defenses did in fact do far better than others in their experiments. In light of the fact that their world size was woefully small, the authors work would have been substantially more humble in terms of acknowledging the effectiveness of some defenses, and should have spent more time focusing on why some defenses did better against some classifiers, what the overhead costs were, and what classifier features were most impacted by each defense. - It does not give statistics on which sites suffer high rates of misclassification.

Even in their small world size, is it likely that they stumbled upon a few pages that ended up consistently misclassified. Which were these? How often does that happen out of arbitrary 128 page subsets? - Features are evaluated, but not in terms of their contribution to accuracy.

There are several standard ways of evaluating the contribution of features to accuracy under various conditions. The authors appeared to employ none of them.

Literature Review: Xiang Cai et al

Title: Touching from a Distance: Website Fingerprinting Attacks and Defenses

This work also attempts to evaluate several additional defenses against the website traffic fingerprinting attack, proposes a Hidden Markov Model extension of the attack to classify web sites in addition to pages, and also attempts to evaluate the BuFLO defense from the "Peek-a-boo" paper, as well as a lower-overhead variant.

On the positive side, the following useful contributions were made:

- A low-resource "congestion sensitive" version of Dyer et al's BuFLO defense is presented.

This defense is also tunable, and deserves a more fair evaluation than was given to it by its own creators. Hopefully they will follow up on it. - An automatic feature extraction mechanism is built in to the classifier.

The work uses an edit distance algorithm to automatically extract features (pairwise transposition, insertion, deletions and substitutions) rather than manual specification and extraction.

However, this paper also shares many of the Peek-a-boo paper's shortcomings above, and has some of its own.

- Minimal edit distance classifiers are ideally suited for a closed world.

The DLSVM classifier finds the shortest edit distance between a single testing instance and the model instances from training. This is a useful heuristic for a closed world, where you know that your training instance will match *something* from your model, but how well does it fare when you have to tune a cutoff to decide when a given traffic stream's edit distance is too large to be among your censored target pages? It seems likely that it is still better than Panchenko's classifier in the open world, but this has not been proven conclusively, especially since the effect of site uniqueness on the classifier was not examined. - Glosses over effects of defenses on edit distance components.

Even though edit distance classifiers do not have explicit features, they still have implicit ones. It would be useful to study the effect of low-resource defenses on the most information-heavy components of the edit distances. Or better: to analyze how to tailor their BuFLO variant to target these components in an optimal way. - Defenses were not given a fair analysis.

In the specific case of both Tor Browser's pipeline defense and HTTPOS, an analysis of the actual prevalence of pipelining and server side support for the HTTPOS feature set was not performed. Nor were statistics on actual request combination and reordering given, nor were the effects on the feature components analyzed. - Navigation-based Hidden Markov Models are user-specific, and will also suffer from Garbage-In Garbage-Out false positive properties.

While a Hidden Markov Model would appear to provide increased accuracy by being able to utilize multiple observations, the reality of web usage is that users' navigation patterns are not uniform and will vary by individual and social group, especially for news/portal sites and for social networks. For example, people often navigate off of Twitter to view outside links, and some people share more links than others. It is quite likely that the HMM will consider any link portal (or any repetitive background network activity) that has an occasional false positive match for Twitter to be mistaken for such intermittent Twitter usage.

Literature Review: Tao Wang and Ian Goldberg

Title: Improved Website Fingerprinting on Tor

This paper improves upon the work by Cai et al by statistically removing Tor flow control cells, improving the training performance of the classifier, and by performing a small-scale open world study of edit distance based classifiers. It also provides some limited analysis of difficult to classify sites.

The paper has the following issues:

- A broken implementation of Tor Browser's defense was studied, despite warnings to the contrary.

Last year, we discovered serious issues with the HTTP Pipeline randomization defense that were introduced during the transition from Firefox 4 to Firefox 10, and that other issues may have been present in the Firefox 4 version as well. These issues were corrected during the transition to Firefox 17, and the pipeline randomization defense was vastly improved, but the authors still chose to evaluate the broken version, despite our offers for assistance. Moreover, like previous work, an analysis of the actual prevalence of server-side pipelining support and request combination and reordering was not performed. - Small world size.

This paper studies a smaller closed world size than the previous edit distance based work (100 pages instead of 1000), and uses only 1000 pages for its open world study. - Target site types were not varied in the open world.

Unlike Panchenko's work, the types of sites chosen as censored targets were fixed, not varied. This makes it hard to evaluate the effects of types of sites with either very distinct or more typical traffic patterns on the accuracy of their classifier.

Source code is provided, however, so it may be possible to revisit and correct some of these issues, at least.

Concluding Remarks: Suggestions for Future Work

This post is not meant to dismiss the website traffic fingerprinting attack entirely. It is merely meant to point out that defense work has not been as conclusively studied as these papers have claimed, and that defenses are actually easier than is presently assumed by the current body of literature.

We believe that the theoretical and practical issues enumerated in this post demonstrate that defenses do not need to be terribly heavy-weight to be effective. It is likely that in practice, relatively simple defenses will still substantially increase the false positive rate of this attack when it is performed against large numbers of web pages (and non-web background traffic), against large volumes of Tor-like traffic, against large numbers of users, or any combination thereof.

We therefore encourage a re-evaluation of existing defenses such as HTTPOS, SPDY and pipeline randomization, and Guard node adaptive padding, Traffic Morphing, as well as the development of additional defenses.

It is possible that some types of pages (especially those on video sites, file locker sites, and sites with very large content elements) may make natural false posties rare, especially when classified among smaller, more typical pages. For instance, it is unlikely to be possible to generate false positives when the classifier needs only to distinguish between pages from Wikipedia versus Youtube, but it is likely that generic large content and video downloads can be obfuscated such that it is hard to recognize the specific video or download site with minimal relative overhead.

As in the work done by Panchenko, we also suggest evaluating each of your classifier's explicit or implicit features for their relative contribution to overall accuracy (especially among similar classes of sites) as this will help guide the padding and obfuscation behaviors of any defenses you or others might devise. The high-information component features or edit distances can be analyzed and used as input to a statistically adaptive padding defense, for example.

In any event, please do contact us if you're interested in studying these or other defenses in Tor Browser or Tor itself.

If you are not interested in helping improve the defenses of Tor, do not have time to perform such evaluations in a thorough manner, or have already previously published a website traffic fingerprinting attack paper yourself, we request that you publish or at least provide us with the source code and the data sets involved in your attack, so that we or others can reproduce your results and evaluate potential defenses as well.

Concluding Remarks: Dual Purpose Defenses

It turns out that some defenses against the website traffic fingerprinting attack are also useful against the end-to-end correlation attack. In particular, defenses that increase the rate of false positives of website traffic fingerprinting using padding and other one-ended schemes is very likely to increase the rate of false positives for end-to-end correlation, especially under situations where either limited record-keeping capacity, sample-based analysis, or link-level encryption reduce connection and inter-packet timing information.

If a defense introduces false positive between many different web pages in website traffic fingerprinting by manipulating the traffic patterns at the entrance of the Tor network but not the exit, it will be very likely to introduce false positives during correlation between the entrance and exit traffic of simultaneous downloads of these same pages. As in website traffic fingerprinting, it turns out that even a small amount of false positives will frustrate a dragnet adversary attempting end-to-end correlation.

End-to-end correlation is a much more difficult problem, and we may not ever solve the problem of repeated observations. However, we likely can increase the number and duration of successful observations that correlation attacks will require to build high confidence, especially if the user base grows very large, and if the web moves to higher adoption rates of TLS (so that HTTP identifiers are not available to provide long-term linkability at exit nodes).

Promising defenses include Adaptive Padding, Traffic Morphing, and various transformation and prediction proxies at the exit node (which could also help performance while we're at it).

Comments

Please note that the comment area below has been archived.

[Reserved for the follow-up

[Reserved for the follow-up points I want to make once Mike finalizes the main text.]

I've thought for years that

I've thought for years that Mike Perry is the pseudonym of a team of best-in-field academics.

Nope, just me and Zombie

Nope, just me and Zombie Steve Jobs here.

hee hee.. Excellent work for

hee hee..

Excellent work for one guy. Hopefully you are applying some of that same horsepower (and part of the Tor Budget) toward elaborate self preservation measures (and Mr. Dingledine). We need you both around for a long time.

You and Tor are probably safer having published this though...

Something cute otters should

Something cute otters should consider when making "point-click-publish" webpages.

'Tao Wang and Ian

'Tao Wang and Ian Goldberg

Title: Improved Website Fingerprinting on Tor

A broken implementation of Tor Browser's defense was studied, despite warnings to the contrary. '

This hurts the reputation of Ian Goldberg. For me this has a huge impact on how I perceive his work, which I considered brilliant before. Please review any suggestions made by him or contributed somehow for some sort of negative bias.

Great!

Great!

Is there some traffic data

Is there some traffic data that people have produced that I might use for my own study?

My doubt has nothing to do

My doubt has nothing to do with the post, it is safe to perform a download tor browser in a. Iso linux http, I say it is possible the exit node modify my download the files contained within. Iso '. Or is it possible to modify the exit node dns eg "https://www.facebook.com" url is correct, but the number is wrong ip?. Where can I ask these questions on this website?

I

I suggest

https://tor.stackexchange.com/

or

https://www.torproject.org/about/contact

for your Tor questions.

One longer term solution is

One longer term solution is to route traffic in layers of nodes, so that replacing every entry- and mid node there is a layer of nodes. Client is connected to, for example, 4 entry nodes simultaneously, and all of those are connected to 4 mid nodes in the next layer so there is 16 connections between them, and traffic is mixed in random size parts when moving between layers. Those parallel streams are combined in exit node. One entry node can have 1/8, 1/6, 1/4, 1/3 or 1/2 fraction of the data without being able to know the fraction by itself. If entry layer nodes have 10%, 10%, 10% and 70% parts of traffic, exit node may see that same traffic coming at it in 25%, 25%, 10% and 40% size parts, because it was mixed on the mid layers.

Tor browser could have

Tor browser could have option for users that an image has a 50% probability of being downloaded automatically and the rest can be downloaded by clicking. This is a hybrid option between allowing and not allowing images.

Or the probability is user adjustable between 10% and 90% but always same for one website in one session.

Could we have a system

Could we have a system specially integrated for tor, that enables people to send a list of URLs and few minutes later get them all in one .zip packet from which they can then read the pages offline? Maybe also bit of recursive fetching so that all links on the requested pages can be fetched too if wanted. This is not for end to end encryption, but even if the sites have https option, for some the threat model is such that it would be better to have just site to exit node encryption before tor encryption if it means that this kind of fetching is possible. The exit nodes might want to ban images or put a size limit for files...

tor browser could have optional kilobyte limit or pixel count limit for pictures that can be downloaded automatically. Adversary would not know what limit the user has chosen. Default limit could be randomized between 200kB and 1000kB, and/or million pixels and 10 million pixels.

Also, for wikipedia people should consider using okawix.

1. The adversary is

1. The adversary is interested in...

2.The adversary is interested in...

3. The adversary is interested in...

4. The adversary is interested in databasing every single web page that every TOR user visits.

I'm Tao Wang, lead author

I'm Tao Wang, lead author for one of the recent works discussed here. I'm here to offer my point of view. I'm first going to address the main issue - "What can we do with WF, really?" I'm then going to offer a point-by-point critique, especially in defense of our work.

Mike tries to show that WF is no threat by showing that it doesn't do very well if it tries to mark every user as suspicious if the classifier returns "yes" on one of the user's page loads. Why would it do that? What is the problem actually being addressed here? Let's say the problem was "One out of 1000 people visited the site once, in 1000 page loads each. Which one out of the one million page loads was that?" This is an incredibly difficult problem, and not being able to answer correctly really doesn't say much. We would also be using a different classifier (one with a ranking methodology, preferably). We would certainly not be arresting 865 of those people.

I think it's a good point that website fingerprinting does not (yet) lead to complete privacy loss; it is not proven that the attacker will almost always know exactly what you're doing. It is right for Mike to repeat this message to ensure that people do not misunderstand this work. But here I'll talk about some scenarios where I think any dissident or whistleblower will be alarmed to know that the attacker can do very well with current methodology. Let's say the attacker has website fingerprinting attack that achieves 95% true positives (says "yes" when you're accessing a sensitive site) and 0.2% false positives (says "yes" when you're not accessing a sensitive site):

1. Narrow down suspects for observable acts (e.g. posting a blog post, doing something on facebook, tweeting). Realistic application: Suppose you want to know who out of 1000 people wrote the damning blog post you saw, criticizing the current government, and you had the traffic of these 1000 people. You know when the blog post was written, so let's say you have 1 instance from each of these people at that time. 1000 is not a small number for the set of people who were using an encrypted channel with proxy at the same time under a government - for example, Egypt. Passing that through the classifier, you are likely to get the actual writer as well as around 2 other writers. You don't know for sure who wrote it, but much more likely than not, just one more observation will let you make an arrest - the confidence increases quickly with each observation.

2. Know that you've visited the site in some range of time. If the variance on your false positive rate is low enough, you could say with high confidence that a client has indeed accessed a page during some period of time (but not exactly when or how often). As this variance should be computed over different pages or sets of pages, a low variance implies that there are no or few other pages which are frequently misclassified as the monitored pages (if they are, it would drive up the variance). Realisitc application: Suppose you ban all pornography in your controlled region (nation, company, whatever) and many people use Tor to visit ponographic sites. For one user for example, 0.5% of his web page loads are pornographic sites. You can know he is doing this, because you know the false positive rate on your classifier is very unlikely to be that high. You can then proceed with punitive acts.

3. Know when you've visited a site, if you visit the site often enough. If we say that the client visits the monitored site at 0.1% probability, then a 0.2% false positive rate will make a pretty crappy classifier for determining when the client visited the site (although you could still achieve the goal in point 2 because you'll observe a 0.295% rate there). But if the client visits it at 2% probability, then such a scheme would answer "yes" for around 2.1% of all site visits, out of which 1.9/2.1 were in fact correct. A 2% chance of visiting one monitored site is maybe optimistic for the attacker, but an open-world classifier can be trained to monitor a high number of sites, and if the same false positive rate holds, then we'd expect a much higher base rate. Of course, the same false positive rate is not likely to hold without a better algorithm. The algorithm would also know when you just aren't visiting the site often enough for it, so it could recognize this fact and hold no confidence in its "yes" classifications.

4. If I'm just trying to block a site on Tor, even applying the classifier naively would give me a very high accuracy of doing so when you access the site with 0.2% collateral damage.

Here's a point by point critique.

>Website traffic fingerprinting attack papers assume that an adversary is for some reason either unmotivated or unable to block Tor outright, but is instead very interested in detecting patterns of specific activity inside Tor-like traffic flows.

I think Mike is trying to make it sound like this is a ridiculous adversary, but we all know that making Tor difficult or costly to block is an active research field; furthermore, convincing people with sensitive information (whistleblowers, dissidents) that they should use Tor to communicate and then catching them doing so is clearly worthwhile. If I tell a dissident "you can post this article on your blog, but know that the government almost certainly knows you're doing it even if you're on Tor", it is likely self-censorship would occur. From another perspective: if website fingerprinting (WF) is a realistic threat and cannot be defended against, why even use Tor's architecture? Since the entry guard can perform WF on the client, the client's privacy is reduced to just using encryption with one untrusted hop.

>It turns out that the effects of all of these factors are actually observable in the papers that managed to study a sufficient world size.

I observe that up to 1000 web pages there is no change. I've never heard of the majority of web pages after the 200th. How many is enough? If I ran 5000 web pages, surely someone can still claim it is not enough.

>It is also clearly visible in Panchenko's large-scale open world study that increasing the world size contributes to a slower, but still steady decline in open world accuracy in Figure 4 below.

This is not what Figure 4 means. Figure 4 refers to increasing the number of instances the attacker trains on. It shows that if the attacker trains on more instances on Panchenko's SVM, the attacker trades off lower true positives for lower false positives. As this is the number of training instances, the attacker can very well say that they are satisfied with 2,000 and cut it off there, if the attacker believes it provides a good balance between true positives and false positives. I don't know what "world size" means (typing "world size machine learning" in google only gets me to something Mike wrote, so I assume Mike made up the term), but I'm pretty sure this isn't what Mike wanted to illustrate.

There is no result on what would happen if you allowed the client to visit a larger set of web pages. Why? I don't know why Andriy Panchenko didn't do it, but I can explain why I didn't do it - because there's no good reason why the accuracy would change. In fact, if the false positive rate of the client visiting 1,000 instances of the top 1,000 web pages is A, and 1,000 instances picked uniformly randomly of the top 1,000,000 web pages is B, then A is much more representative of reality than B. Theoretically the relationship between A and B is not predictable. In other words: If your time and resources allow you to let the client visit X pages, those should be the X most popular pages in order to cover as much traffic as possible, instead of a random size X subset of Y pages, which produces a less meaningful number.

>These statistics (which have been examined in other computer security-related application domains of machine learning) show that false positives end up destroying the effectiveness of classification unless they are vanishingly small (much less than 10^-6).

I would be cautious to generalize the one specific use of machine learning - intrusion detection systems - to all papers on security (strictly speaking website fingerprinting isn't even about security). Why is that specific number important? It is not, unless the base rate of false actions is on or greater than the order of 10^6 of that of true actions. That is not directly applicable to website fingerprinting. It is obviously not true for all classifiers that are applied in the field of security either.

>As you increase the world size, the likelihood of including a page that matches a traffic stream of your target page also increases.

Yes, there will be more false positives. But the total world size increases, giving you possibly the same false positive rate. Is there a good argument as to why the false positive rate would change?

>Beyond this, each page actually also has at least 8 different common traffic patterns consisting of the combination of the following common browser configurations: Cached vs non-cached; Javascript enabled vs disabled; adblocked vs non-adblocked.

Yes, this is a problem for the attacker. But if I'm not mistaken, to defend against browser fingerprinting (not WF), Tor Browser users have the last two settings exactly the same, and a disk cache is not kept. So whenever you close your Tor Firefox window and re-open it, you become susceptible to WF with any first access to each page. There's also the hypothesis that if the client is applying a setting that significantly affects her traffic, then the attacker can guess the setting and train on web pages using this setting, but this is certainly not done (and it would not be real-time classification). Cai et al. also addressed the cached scenario in more detail.

>A broken implementation of Tor Browser's defense was studied, despite warnings to the contrary. '

>Moreover, like previous work, an analysis of the actual prevalence of server-side pipelining support and request combination and reordering was not performed.

>>>This hurts the reputation of Ian Goldberg. For me this has a huge impact on how I perceive his work, which I considered brilliant before. Please review any suggestions made by him or contributed somehow for some sort of negative bias. (user comment)

I feel like I have to address this point specificially. It was the then-current implementation applied to Tor at the time when we wrote the paper, I didn't just pick up some random "broken" implementation. Mike pushed forward with the new defense one month after I told him that the old one was ineffective. The old implementation has been used for almost two years. This strongly suggests that measuring the effectiveness of the old (again, then-current) implementation was interesting research work that had real impact. And now Mike turns around and accuses me of using a broken implementation.

Mike only told me in private communication - after we'd finished the paper - that the old defense was broken, lacking proof or evidence. I estimated that, given my rather limited infrastructure, if I were to apply the new defense, collect a whole new data set with it, and measure it again, it would take around three weeks. What if Mike then told me this one was still broken and he fixed it again? Isn't the burden of proof on Mike Perry to show that this new defense is now much more effective against the WF attacks of the day? I feel that this evidence is necessary for any claim that the old implementation is more "broken" than the current one.

The prevalence of server-side pipelining support is addressed by the HTTPOS paper by Luo et al. Since this work is already done I don't think Cai et al. or myself should be faulted for not repeating it.

>Promising defenses include Adaptive Padding, Traffic Morphing, and various transformation and prediction proxies at the exit node (which could also help performance while we're at it).

>We therefore encourage a re-evaluation of existing defenses such as HTTPOS, SPDY and pipeline randomization, and Guard node adaptive padding, Traffic Morphing, as well as the development of additional defenses.

Traffic morphing actually has almost no effect whatsoever on Tor. It only morphs TCP packet size distributions, which should be very similar between different pages due to Tor's fixed-length cells. Adaptive padding only changes timing information and none of the latest attacks even look at timing information, so it would literally do nothing at all besides the extra dummy packets (so it's reduced to a rather naive defense that sends dummy packets randomly and infrequently). HTTPOS does nothing to Tor or the latest attacks either, since again it's playing with packet sizes, which are useless on Tor. HTTPOS's particular contribution to the field is showing that the client can do a lot of simpler WF defenses on her own, without any support from proxies or the end server. The infrastructure is useful when the client can't rely on anyone else on the Internet, but we can implement defenses on Tor nodes or bridges much more effectively (and do a lot of things a client can't do by herself). I've written most of this to Mike a few months ago.

>>>Is there some traffic data that people have produced that I might use for my own study? (user comment)

Yes, my source code that Mike kindly linked contains most of the data we collected and used as well. I also got Cai et al.'s data when I asked them for it. Liberatore and Levine's data is here:

http://traces.cs.umass.edu/index.php/Network/Network

under "WebIdent 2 Traces".

With perhaps one exception,

With perhaps one exception, I believe my points in the blog post still withstand your responses above.

The one thing I will concede is that if you have enough prior information both to timebox the duration over which your attack is applied (as you say, perhaps by using a known-valid timestamp from a blog post) and you have a way to reduce the number of suspected clients, then you do substantially reduce the base rate of activity, and this does reduce the effect of false positives on the total number of accused (ie it does increase the Bayesian detection rate). This is a lot of prior information though, and is a very narrow case on which to base the argument that all potential defenses against the attack are broken.

With respect to the repeat visit idea in points 2 and 3 from your reply, though: Beyond the math from the blog post about the dragnet effects of the Binomial distribution (which still applies here), it is also the case that without prior information on each specific user's viewing habits, all the adversary knows from frequent, multiple matches is that the user is frequently visiting one (or likely multiple) sites that have a classifier match for the target site (either true or false positive). In other words, there is little reason to believe a-priori that an adversary's target site is any more likely to cause repeated visits than any other sites that also happen to have false positive matches for it.